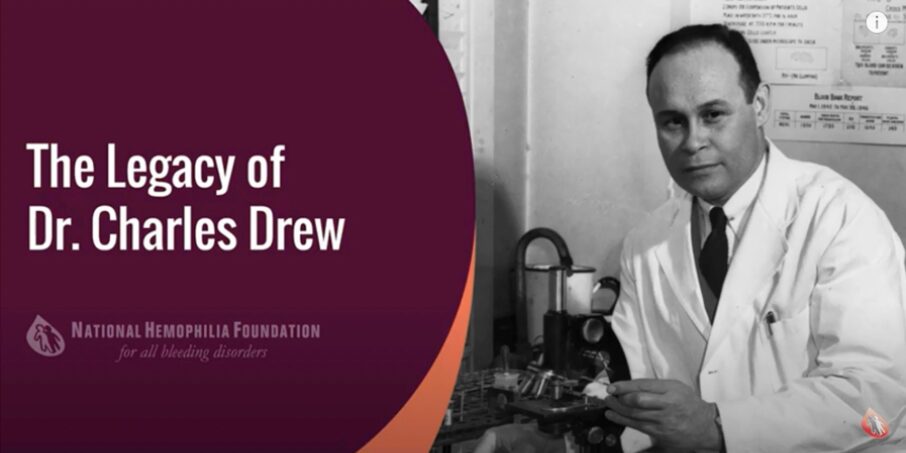

Honoring the Legacy of Dr. Charles Drew

NHF staff and experts share insights on the remarkable impact of Dr. Charles Drew.

June 3 is the birth date of the late physician and researcher, Dr. Charles Drew. Dr. Drew is remembered for his legacy in creating valuable techniques and processes in blood storage and blood transfusion that are still used today. He is also heralded for his efforts in health equity and racial justice in the care of African American and Black patients, and for promotion the training of Black and African American physicians.

In a new video, experts share insights on Dr. Drew’s remarkable contributions. In this transcript and related video, experts include NHF’s vice president for health equity, diversity, and inclusion, Dr. Keri Norris; as well as Dr. Steven Spitalnik, Co-Director of the Laboratory of Transfusion Biology at Columbia University; Rob Wallace, STEM Education Specialist, The National WWII Museum; and Fabrizio Saraceni, Laboratory and Pathology Director at UC Davis.

Click here to watch the video.

Dr. Keri Norris:

Dr. Drew created a path for himself in a space for which other hematologists [and physicians] could follow in his footsteps and even improve upon what he initially started.

Dr. Steven Spitalnik:

Dr. Drew is well recognized as one of the founders of blood banking and transfusion medicine, particularly for his work during World War II. During World War II, collecting and shipping plasma to Europe was necessary, and, before Dr. Drew’s innovations, the only type of blood that could be stored was whole blood.

Fabrizio Saraceni:

Before WWII, blood storage was problematic because it could only be stored for a few days, about a week. And because of that, it could not be replenished fast enough.

Dr. Drew, in his studies, developed a process to separate the blood into cells, with plasma being the liquid portion. But plasma did not have the oxygen carrying capacity of red blood cells, even though it provided clotting factors, which would stop bleeding, which was especially helpful for victims of trauma and in the blitzes of 1939 and throughout the next few years of war.

Rob Wallace:

He did his own research on how to do it [separating blood into plasma and cells]. But then he also sort of pulled together everybody else’s ideas and made it so that it could operate at scale. He had to really do it in tough times, because he was developing the blood bank to send to England during the Blitzes around Britain.

Fabrizio Saraceni:

That was a really big challenge there, the ability to separate the red cells from the plasma allowed shipment of plasma to England, for the war effort. And this then led to Dr. Drew establishing the blood centers for the American Red Cross.

Rob Wallace:

Dr. Drew had to go to school in Canada [at McGill University], because the medical schools in the United States that would admit him wouldn’t allow him to have practical training, because he might, you know, have to work on a white patient. And they didn’t think that the patients would be comfortable with that. And some of them weren’t comfortable with that.

When he finished his degree, he had an idea of what he wanted to do, which was to study blood and develop a system for transfusions. And, you know, he had to fight his way into that postdoctoral program. He was the first African American to enter that program and to get through that program [at Columbia University].

Dr. Keri Norris:

In his plight to study medicine while not having some of the best medical equipment and laboratories and things of that nature, he had to work with what he had. He created a path for himself and a space for which other physicians and researchers could follow in his footsteps and even improve upon what he initially started.

Fabrizio Saraceni:

He was also a leader in health equity and racial justice. Dr. Drew set the scientific standard by demonstrating that a person’s race did not have any effect on whether or not they could receive blood from other ethnicities.

Rob Wallace:

Starting a quality medical school program at Howard University was important to him. He went to do what he really wanted, which was to teach African American students how to be doctors. I think his most lasting impact in general, though, is really he himself as a human being and physician demonstrated commitment and perseverance to a career in academic medicine.

Dr. Steven Spitalnik:

He was a surgeon and obviously surgeons use a lot of blood transfers during transfusion. And so, he’s well recognized in my field, but I think his real lasting contribution is as a role model, and someone to admire and someone to try to live up to.

Dr. Keri Norris:

As a public health professional, I’m inspired by Dr. Drew’s tenacity. In looking at a lot of the barriers that are sometimes in the way for people of color for women of color, I’m inspired by his tenacity to just keep charging ahead and keep forging ahead. He inspires me to keep creating my own path and staying the course for what it is I want to do with my career.

Dr. Steven Spitalnik:

Today, we remember Dr. Drew by knowing that our care for trauma patients has advanced based upon the foundation that Dr. Drew established, starting with the foundation of separating blood into red cells and plasma. And research has gone on even further to advance those storage capabilities of blood products.

After finishing his residency, he came to Columbia [University] to pursue laboratory research. What’s remarkable to me — and from a very personal point of view — is his dissertation was about the storing of red blood cell red blood cell storage in the refrigerator, particularly around what happens when you store the blood in the refrigerator and how that can be improved. And in fact, that’s exactly what my laboratory does now. His research was beautiful, and was really cutting edge at the time. Some of his approaches and findings are still applicable today.

Dr. Keri Norris:

Society can do a better job of celebrating Dr. Drew with those who are in the fields of blood transfusions, and who work in hematology and pathology in particular, giving credit where credit is due. It starts with small things there and then larger things, like donating to foundations that are named after him and being able to carry on that work.

Source: National Hemophilia Foundation, June 2022